by Katy Ibsen, contributing writer

The American Mold Builder

It’s no secret that in today’s manufacturing industries, including moldmaking, a skills gap of trained manufacturing employees is occurring – and expected to get worse. According to a 2015 report sponsored by The Manufacturing Institute and Deloitte, 3.4 million manufacturing jobs will need to be filled by 2025, of which 60 percent will be unfilled due to a talent shortage. The statistics are staggering – and causing a ripple effect of response within the industry.

Rick Hecker, president of Michigan-based Eifel Mold & Engineering, an auto mold manufacturing firm started by his father in 1973, has seen the deficit firsthand. “Right now, there is definitely a skills gap of about 20 years where people didn’t come into the trade,” said Hecker. “The only way we can do anything about it is through programs like what we’re building with the high schools. We have to bring kids into our shop and let them see what we’re doing.”

The report continued: “The manufacturing industry can’t solve all of its talent challenges on its own. Manufacturers should build robust community outreach programs, design curriculums in collaboration with technical and community colleges, and continue to invest in external relationships that help attract talent.”

Two manufacturers, members of the American Mold Builders Association (AMBA), have done just that – created programs from which they can recruit new, younger talent.

If you build it, they will come

Hecker is one of many manufacturers who has introduced a unique shadow program into his company and, therefore, the industry. Innovative companies seeking to close the gap are partnering with local high schools, community colleges or trade organizations to illustrate the opportunities of a career in manufacturing.

“I think there’s been a perception over the years for a lot of these young kids where they think the only way they can make it is if they go to a four-year college,” said Hecker. “That’s what has been preached and sold in high schools, but not everybody needs to go to college. There are other career paths.” Hecker noted that demonstrating the attractiveness of making a decent living wage, being trained on state-of-the-art machinery and learning skills to support evolving technology has helped Eifel combat the skills gap.

Several years ago, Hecker began leading a manufacturing and CAD advisory board that brought together local business partners and the Southwest Macomb Technical Education Consortium (SMTEC) in Macomb County, Michigan. SMTEC consists of four area high schools receiving manufacturing and CAD training. As an advisory member of the SMTEC consortium, Hecker witnessed area schools seeking advice on how to offer curriculum that would make their students more employable, and the business partners were ready to help.

“We started a job shadowing program with the high school. We brought kids in here, probably about 12 to 15 students, and held a class for them. We showed them what our designers do and encouraged these kids to take a CAD class during school. Then, we showed them how to machine something,” said Hecker. This allowed the students to experience the “art to part” process of design and manufacturing.

With much success, the half-day job shadow program eventually evolved into a co-op program, where students could apply for part-time work in the afternoons. This eventually evolved into a conduit for hiring recent graduates.

Eifel currently employs three recent high school grads and is subsidizing their associates degrees in mold building at Macomb Community College in Warren, Michigan. Michael Owen is one such employee. Owen graduated high school after participating in Career and Technical Education (CTE) courses. It was his shop teacher who recognized his potential in mold manufacturing and encouraged him to apply to Eifel. Two weeks later, he had a job.

When asked what he enjoys most about the position, Owen said, “The older people here really like to share their knowledge with the younger people. It makes coming into work easier because I know there are people who will show me how to do something.”

Mentoring has naturally become an important part of the shadow program, and Owen confirmed that Eifel feels more like a family than a job. Hecker can attest to the benefits of that, especially when it comes to creating a desirable working environment for younger generations.

Mold Maker Professional for a Day

Hecker isn’t alone in the effort to decrease the skills gap. Timothy Myers, general manager at Century Die Company, LLC, in Fremont, Ohio, also has seen promising results from implementing shadow programs for high school students.

Century Die was founded in 1946 and focuses on extrusion blow mold tooling for packaging. However, Myers had a wake-up call in 2011 – just a year after he and a team of investors purchased the company – when he realized the median age of employees in his business was 54.

“It was kind of scary when I realized the average age was as old as I am,” said Myers. “I’m not ready to retire, but it’s on the horizon. I had to ask myself how we were going to keep the business going. What were we going to do?”

Myers knew the perceptions among students about manufacturing: a college degree was the only way to begin a career; factories were dirty. He wondered, “How do we give these kids an opportunity to see what it’s like inside a manufacturing facility? That it’s not the old-fashioned, dirty, greasy factory that is overly hot in the summer and overly cold in the winter? That doesn’t exist anymore.”

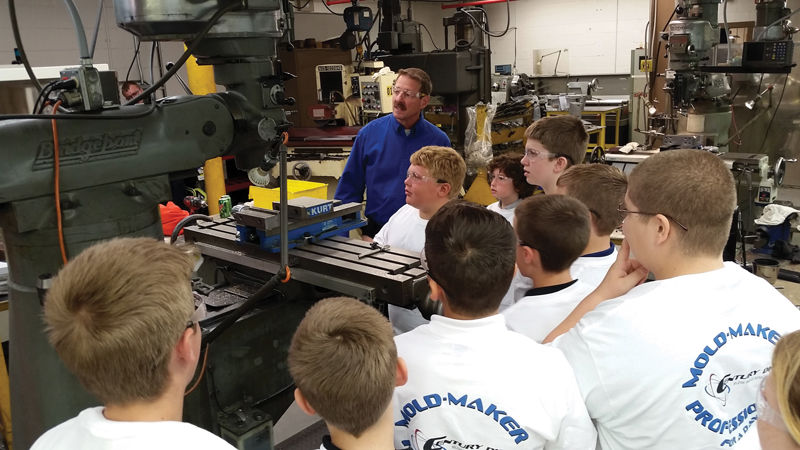

Myers knew he would need to reverse that misconception by bringing in students. “We’re a machine shop, and we wanted to bring these kids in to showcase the skilled trade side of machining and mold- making,” he said. To start, Century Die created an all-day shadow program in cooperation with local schools. Students, grades 7 through 12, would partake in the Mold Maker Professional for a Day program by shadowing employees.

“When I originally started the program, I was not the favorite person,” he said. “The guys on the floor would ask why I was bringing a seventh-grade girl in for shadowing when there was work to be done. They were kind of mad, almost to the point of mutiny.”

As a result, Myers and the school amended the concept. Now, students (two to four at a time) spend 20 minutes in each department of the company, not just machining. They meet with project managers, engineers, purchasing agents, IT support, the comptroller – all the employees who support the factory’s core functions.

“After the job shadowing, we ask the students what the best part of the day was for them,” said Myers. “They tell us they liked being engaged with the people on the floor and all the different conversations … it’s an eye opener for them.”

One major outcome for Century Die has been increased enrollment in its four-year State of Ohio Apprenticeship program, in partnership with the state government. It’s an initiative created to help those entering the workforce learn skilled trades and avoid student debt. When students conclude the apprenticeship, they receive a certificate for their specialty, such as moldmaker or machinist.

“The students start out working on manual machinery or doing tasks that aren’t too technical,” said Myers of the well-rounded education. “They spend time throughout the entire facility learning in different areas, and they should be able to do most anything we have in here by the time they complete the program. They may not be the best at certain pieces of it, but they have an understanding.”

The numbers confirm the value of the outreach programs. Now in its sixth year, the company has seen steady change. Prior to the program, Century Die had a median employee age of 54, employed nine millennials and had no apprentices. Today, the median age is 44, the company employs 28 millennials and nine apprentices are on staff.

“Overall, my goal is to increase awareness out there – to create opportunities,” he said. “There is so much opportunity right here in these kids’ backyard that doesn’t require a traditional “university-style” college education. Some of them don’t need it. Instead, they like to work with their hands. They like to make something from nothing, and they take pride in it.”

When shadowing leads to innovation

With the success of job shadowing programs over the last several years, Hecker has taken Eifel’s mentoring concept a step further – he went back to school. In 2017, the company expanded a local school’s CNC machining center after a fruitful encounter with Dr. Masahiko Mori from DMG Mori.

While Hecker was attending Innovation Days in Chicago, he had the occasion to visit with Dr. Mori about their shared passion in helping young adults explore and train for manufacturing positions. The conversation led to an overwhelmingly generous agreement to place state-of-the-art equipment at Lincoln High School in Warren, Michigan.

“I got to sit down with Dr. Mori for a few minutes and talk about our involvement with the high school,” said Hecker of his local program. “And I said to him, ‘It sure would be great if we could find a way to get a machine in there.’”

Following the conversation and some correspondence, DMG Mori agreed to place a CNC milling machine in the school for a “zero-dollar lease” over two years. As other area companies learned about the gift, they too offered pro bono assistance for installation of the machine and getting the training center up to speed. Furthermore, Hecker applied for an AMMA Grant and received a one-time gift of $10,000 to clear the center of old and outdated equipment and provide training for educators throughout the two years.

Century Die also received grant funding from AMBA to help offset costs associated with the job shadow program.The company also has a popular Green Box Derby event, which invites students and adults to build gravity-powered cars out of recycled materials for competition. One might hope such an event, hosted by a manufacturer, would lead to greater awareness of the industry.

The positive outcomes of job shadow programs within the manufacturing industry are on the rise, and more companies continue to adopt the concept. In addition to potentially decreasing the skills gap, manufacturers are broadening the opportunities for young adults who desire a successful career without attending a four-year university.

“The support we’ve gotten from local businesses has been overwhelming,” said Hecker. “We all see the need to bring young people into our trades, into our skill sets and into our businesses.”

References

- Deloitte, The skills gap in US manufacturing: 2015 and beyond, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/manufacturing/articles/boiling-point-the-skills-gap-in-us-manufacturing.html